“It feels like it came out of a shared community,” the Johannesburg-based South African artist Nolan Oswald Dennis tells Observer about making his U.S. institutional debut alongside London-based Swiss artist Deborah-Joyce Holman in separate exhibitions exploring Black identity. “Deborah and I have known each other for a very long time even though we’re from different parts of the world… that community for me is this kind of African and African diaspora, Black and brown, post-colonial art world.”

In January, their solo shows—Dennis’ “overturns,” which examines decolonization and practices of Black, Queer and Indigenous liberation, and Holman’s Close-Up, which considers the politics of representation of Black and Queer people on the screen, opened at the Swiss Institute in New York. We spoke with the artists about those exhibitions and their impact.

Does it mean anything that this is your institutional show debut in the United States?

Dennis: I think, for me, it’s significant in relation to the history of Black and African presence in America. And so I think it feels meaningful to me to present my work in dialogue with the history of other African people—especially in New York.

And there’s a work in the show called Rememberer (Kgositsile’s Folly). Keorapetse Kgositsile was a South African poet who lived in the U.S. in the ‘70s and ‘80s, so this is, for me, the framework that I think about and the significance of sharing my work in America. Then, of course, there’s the trouble of the U.S., and I think being South African. It’s a complicated time. It’s hard to think about significance beyond solidarity, let’s say.

SEE ALSO: Mattress Factory’s Danny Bracken On Eugene Macki’s ‘Reification’

There’s the belief that shows like these elevate the careers of artists. Obviously the work is also introduced to a new audience—do you have expectations around that?

Dennis: I think for me it’s exciting to imagine that the work is being encountered by people who I would never have the opportunity to connect with through my work. So the show is kind of meaningful to me in this way. But I think the idea of a career in the art world, in the museum world, in this kind of structure, it’s every day less and less appealing. Because it’s every day less and less secure, especially if you’re African. And if you’re from South Africa, and if you have a sexual orientation of a certain type or a political orientation of a certain type, these spaces are not welcoming even in the way that they were maybe a year or two ago. I don’t have this excitement about entering into a kind of professional circulation through these institutions. It’s more scary to imagine what the pushback will be.

What do you mean by that, Nolan?

Dennis: The work that I’m showing is very much rooted in the shared history of anti-colonial struggle in Africa, anti-racist struggle in the U.S. It’s also grounded in the history of Queer liberation, gay liberation and lesbian liberation. And these things are more and more unpalatable than it feels in the public sphere. And more than that, coming from South Africa I’m thinking about liberation and anti-apartheid histories in this time. It’s a difficult time, to be honest, when there’s a genocide happening in Palestine. And there’s a lot of pressure not to be conscious and present and express anything in solidarity with what’s happening. So, this is what I mean by these institutions: they feel more scary than welcoming.

What’s the story behind you both presenting solo shows exploring Black Identity simultaneously at the Swiss Institute?

Holman: I think we have the curators of the Swiss Institute, Alison Coplan [chief curator] and KJ Abudu [assistant curator] to thank for that. I think in terms of exploring identity or Blackness specifically, maybe reaching back to the previous question as well, there might be through lines of that, but at the same time, I would maybe flip it on its head speaking to my work in that I feel like Blackness comes before the gendered and racial elements of the work. And then I’m trying to figure out how those can work with or against specific forms and frameworks, in this case the film that I made. And I’ve been in conversation with K.J. and Alison for maybe a year and a bit before since I did the residency at the Swiss Institute in 2023. The show grew out of those conversations and exchanges.

Dennis: For me, it feels like it came out of a shared community. Deborah and I have known each other for a very long time, even though we’re from different parts of the world.

We have shared a community for coming up on ten years now. And that community for me is this kind of African and African diaspora, Black and Brown, post-colonial art world that kind of exists underneath—maybe underneath is not the best way to put it—but it exists kind of parallel to museums and the bigger art world. And K.J. [Abudu], who was one of the curators of the show, is part of that community, and for me, the exhibition feels like an expression of this underlying, ongoing community of art practitioners. It’s nice for it to emerge and express itself in New York. And then it will express itself somewhere else and in other forms. For me, it’s part of this cycle of community.

Nolan, can you expand on the sculptures in “overturns” being inspired by imagining conversations between Steve Biko, Amílcar Cabral, Toni Cade Bambara and Malcolm X?

Dennis: [The show is projecting] an attitude toward knowledge, toward history, toward somehow bringing things from below, above or overturning, or maybe transforming, the material that we receive from the world—the knowledge, the history, et cetera. And those works that you’re talking about that simulate this conversation, they basically take archives of Black liberation thinkers, Black consciousness thinkers, Steve Biko, the great South African and also Black feminist thinkers like Toni Cade Bambara who were not ever in a direct conversation because of conditions of the time. For example, I’d say all of the people with whom I’m putting Biko in dialogue were not allowed to be published. Their work was not allowed to be shared in South Africa at the time when Steve Biko was alive because of the censorship structure. But nonetheless, they’re in dialogue. Their works are in dialogue, and their values and projects are in dialogue.

The work runs an algorithm that pulls from their archives and then recreates a conversation. For example, Dr. Cabral and Steve Biko have a conversation about time and place. It’s maybe not so much an imaginary conversation as it is a conversation that happened in other forms. Maybe it happened through our inheritance of their work or through the work that other people did with their work. There’s this connection that always has been there, and the work is riding that connection.

Deborah-Joyce, how does Close-Up challenge viewers to consider the inner lives and personhood of modern life subjects appearing on screen?

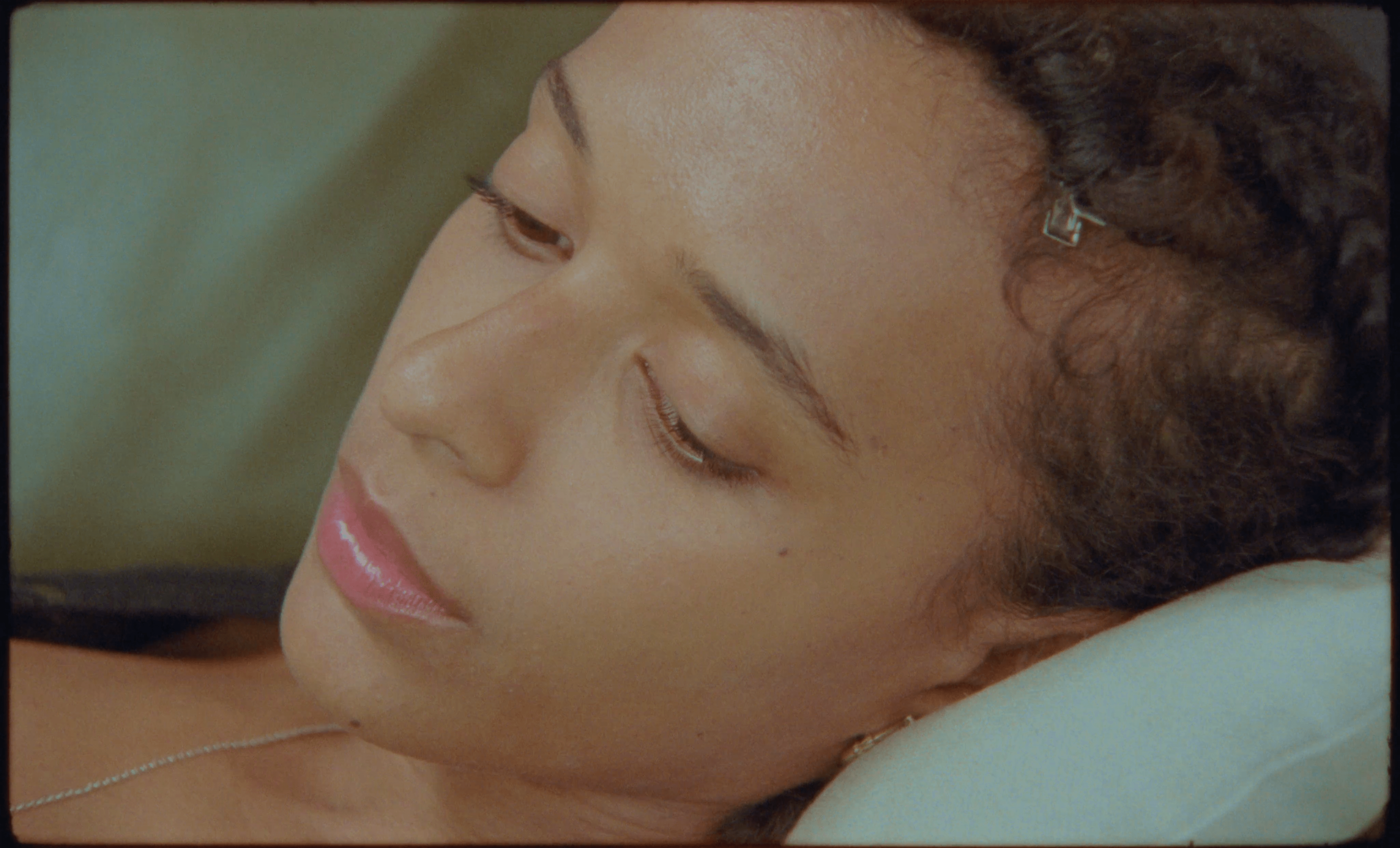

Holman: I’ll start by just saying that in [my] practice, I’m interested in what could be called the broadest concerns or issues between portraiture and anti-portraiture—the relation between the person and the camera and film culture, taking into consideration the context within which it circulates. So Close-Up is a restaging of a previous film that I made the year before. It is gestural, and nothing happens. It’s like there’s no narrative. It’s very anti-spectacular, but it is a very, very precise restaging of a film before. And that oscillates between a portrait of this actress and this character on screen and the opposite or anti-portraiture, in that we don’t actually get any access to the actress’s interior.

There’s maybe a stake of anonymity or something that we don’t get. We don’t, despite what the formal choice of the close-up suggests. There’s no access to the interior. I guess that kind of leads into or speaks to an interest in what is possible within filmic representation or the framework of representation through film—especially as a racialized and gendered protagonist is burdened with.

I often quote this phrasing from Kara Keeling, who talks about representation as being a double bind. On the one hand, being a stand-in for a group of people, and on the other hand, maybe more in the political sense like, speaking for, being the mouthpiece of a group of people, or being the representative of a group of people, in that sense. And, both of those come together in the film. With Close-Up and the previous film, I guess both were our attempts at trying to move away from that huge burden and see what happens with that narrative and those kinds of corner points by which the character can be pinned down or made into a representative when that’s stripped away, what can happen with it.

Are there some similarities in your experiences as Black people, even though you come from and live in different parts of the world?

Holman: I think maybe the relation happens through a shared, or I’m assuming, Nolan, you will correct me if I’m wrong, but maybe a shared interest in projects of liberation and what that can look like, what the strategies are, what the stakes are, what the different, contextual, conditions are. That’s also something that Nolan mentioned in the beginning in terms of it being interesting that we’re all from such different places, including KJ, and the exhibition taking place in a place that none of us are from or speaking from.

And I guess the global relation may happen through a shared experience of the opposite. Often I feel like, you know, what’s the stake or the conversation around Blackness is often had from maybe the flipping of the opposite, which is an experience of being faced with living in a white supremacist, capitalist framework, where, out of which some shared experiences of, I don’t know if I want to say subjugations or prejudice or something come out of. But then, I guess our shape still, once you go deeper, is shared; it becomes a question around ethnicity, not just race.

Dennis: I agree. Blackness and Black experiences are so diverse they really don’t collapse into a single shared definition or a single shared experience. But when you encounter each other, and this is, I’m going to speak in such vague terms, but I think it’s important to say it in this open way. There are things that are quite obviously shared. Those can be bad experiences of existing in the world, but I find more often, it’s a kind of attitude that you see in the work that people do and the way that people move.

And I guess maybe like Deborah said about liberation, it is maybe the important thing that underlies it all, the sense that we will be free. And wherever we are, there’s always this thing that’s a hit on your back, but I don’t know. It’s a very vague thing to say, but maybe the difference between coming from Africa and traveling through Europe or traveling in the U.S. is also an additional kind of experience. But even in spite of that difference, there’s a kind of mutual recognition, and there’s something that you see in each other. It’s a difficult question to answer.

Nolan Oswald Dennis’ “overturns” and Close-Up by Deborah-Joyce Holman are on view at the Swiss Institute in New York through April 13, 2025.

<